Balancing beauty and depth

How do you embrace extravagant beauty and joy without neglecting the humble and serious things that make life meaningful? Plus, Victorian flower language and a pretty and practical London flat.

For my 17th birthday, I hosted a tea party with fine china, fancy sandwiches and handmade conversation cards. The rosebud chintz dishes, family heirlooms, decorated the table and all the food we served was in miniature form. 10 or so teenagers, both boys and girls, sat around the long, rectangular table and chatted. There was a sweet (and maybe slightly comical) air of formality about it. I remember being nervous that people would have fun, especially because I recognized that it was unusual to have such a formal birthday party for a teen.

But this was just how I grew up. I spent the most formative moments of my childhood around my grandparents and great grandparents, people who maintained more formal, traditional practices throughout their lives. I love this part of my childhood because it taught me that even my little life — mostly full of family dinners and time spent at home — was worthy of an important occasion.

For me, there’s always been a pull between wanting things to be special and also staying anchored in the things that matter. It’s not that the two are mutually exclusive: you can be a fun person and also have serious, deep thoughts. Though I love to do things up in style, go all out, overdress and over-plan, I’ve always been aware that too much of a good thing could detract from conversation, connection or making people feel comfortable. This pull between wanting to make things special and wanting to create a relaxed, humble and comfortable environment was on my mind at my 17th birthday party and, to be honest, at every event I’ve hosted since.

The same tension shows up in other areas of my life, too. I love to get dressed up, to wear makeup and to feel beautiful, but I never want to become so fastidious about my looks that I equate my appearance with my worthiness. And I want my house to be beautiful, to decorate it and to use it as a creative playground, but I don’t want to be so caught up in its improvement that I can’t be grateful for the home in its current state.

I’ve read a slew of wonderful books lately that cover this theme, the tension between beauty and practicality, or of beauty and reality. Most of the books were written in the Victorian era and they criticize the culture at the time, which was so obsessed with beauty that more important things (like horrible poverty) were overlooked. In “The Portrait of a Lady” by Henry James, the main character is a steely, stubborn and beautiful young woman who has her eyes so set on her ideal life that she overlooks a whole host of red flags and builds an unhappy life because of it. “The Tenant of Wildfell Hall” by Anne Brontë explores how one woman gave up a wealthy, leisurely life (albeit, with many troubles) to preserve her integrity and hold onto her values. And Thomas Hardy’s “Far From the Madding Crowd” follows another idealistic woman from success to failure and back again, exploring how her idealism shapes her decisions — and the cost of choosing the wrong path. Each book is full of idyllic scenes that convey something deeper beneath all of the beauty.

I find comfort in the way that this question of how to hold beauty with depth spans generations. Forever we have wondered how to enjoy life and embrace all of its fun parts while staying anchored in reality and focused on what matters most.

Today’s newsletter explores a question that has been on my mind lately: How do you embrace extravagant beauty and joy without neglecting the humble and serious things that make life meaningful? Thanks for being here.

FLOWERS AND THEIR MEANINGS

Victorian flower language, decoded

When I read for the first time “The Picture of Dorian Gray” by Oscar Wilde I was fascinated with the meaning conveyed in the imagery of the book. Flowers that the author chose to decorate scenes foretold the Dorian’s future and gave me, the reader, clues to the next plot point. The same is true when I read “Rebecca” by Daphne du Maurier a few months ago. She uses flowers, blood-red rhododendrons, to tell the reader that some mystery is hanging around, waiting to be discovered.

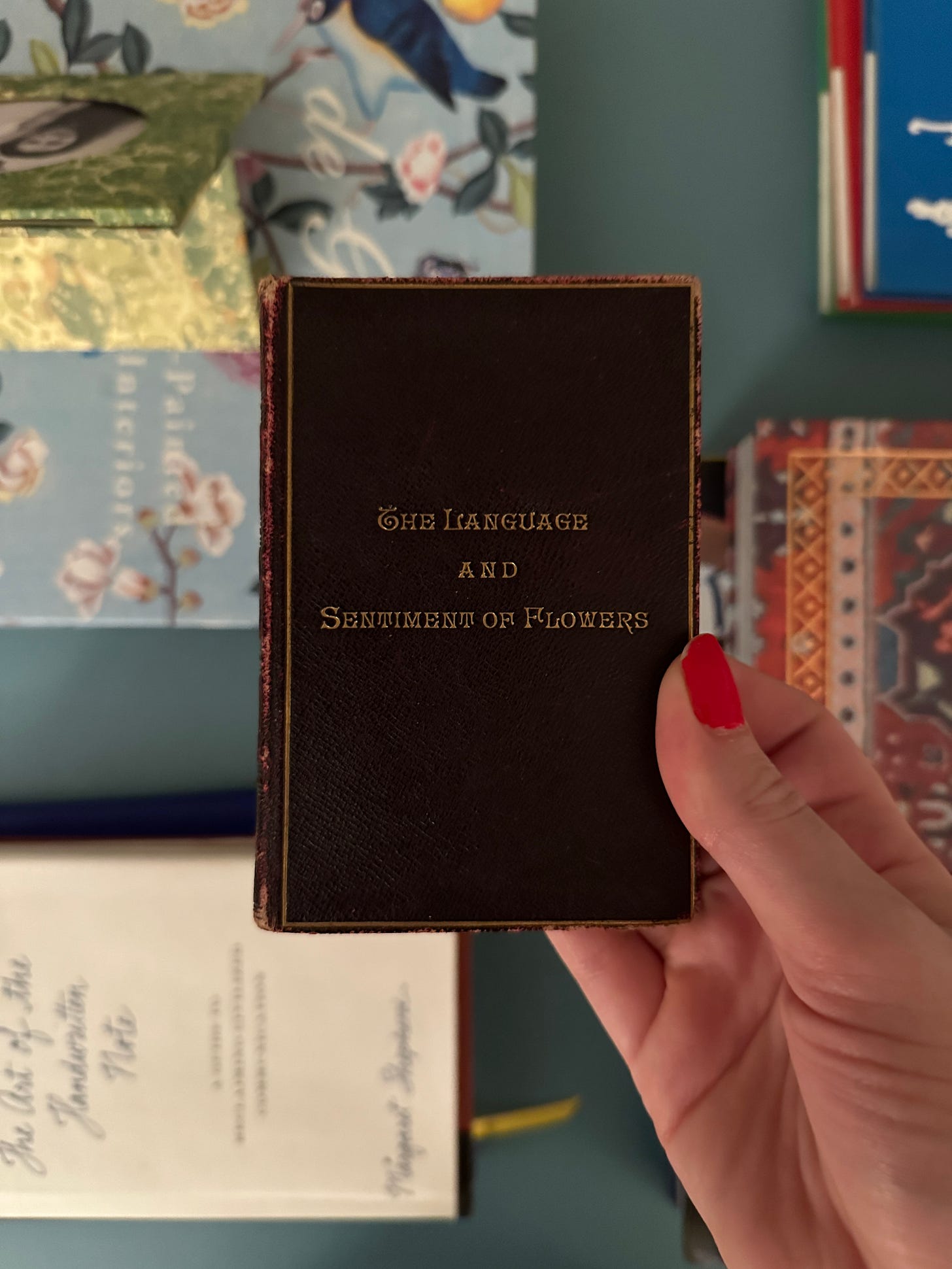

It’s sort of intuitive to associate flowers with certain meanings — red roses, for example, are most often used to express romantic love — but I never understood the depth of their meaning until my grandmother gave me two books about the language of flowers. One of the books may be from the 1860s, if I’m not mistaken, because it resembles this one held by the Biodiversity Heritage Library at the Smithsonian.

In the Victorian era, sending a bouquet of flowers to someone was a way to send a secret message. Japanese lilies, according to the tiny book in my hand, said “You cannot deceive me.” Yellow roses indicated a decrease of love (!) or jealousy. The book is organized first by flower and then by sentiment, meaning that you could decide you wanted to send someone a message of friendship you could flip right to the “F” section and find that an oak-leaved geranium should be sent.

What I love most about this practice is that, to any other person, a flower would have no other meaning than its beauty. I find that much of life is that way: If you don’t know where to look for meaning, you might miss it altogether.

EXCESSIVE BEAUTY

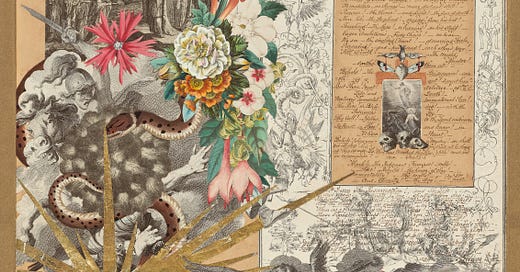

A collage by the artist John Bingley Garland

While perusing the digital collections of the Getty Museum, I came across this collage by John Bingley Garland which dates back to the 1850s-1860s. Instead of sharing my own humble, digital collages with you like I usually do, I wanted to show you this one in detail.

The work looks like a Medieval manuscript with religious motifs and natural elements throughout, and saturated colors coupled with black, white and gray ink. At first glance, the artwork is so busy and colorful that you could easily glance over its darker themes. When you look at it a little longer, you see that the artist pulled together beautiful scrolling details, flowers and angelic scenes alongside a poem about death and art depicting the crucifixion.

Do you see the blue flowers at the bottom of the image? They look like hellebores to me, which represent scandal and calumny (which is misrepresenting someone to harm their reputation). I wonder if the meaning was intentional.

GRIT AND GRANDNESS

When practicality makes beauty bolder

This tiny London flat designed by Carlos Sánchez-Garcia graced the pages of the latest edition of House & Garden magazine and what I loved most about it is the abundance of bright, vibrant color.

With William Morris prints on the walls of the kitchen, pleated fabrics in the cupboard doors and rich textiles throughout, it somehow feels decadent and humble and fancy and comfortable all at the same time.

I like the pairing of a happy, sunny yellow with the rich reds and browns in this room. The designer is quoted in the article noting that, while storage is always top-of-mind when decorating a small space, it doesn’t need to be the primary focus. “You can do whatever you want in design, but you have to have a reason,” he says in the article.

WELL-DRESSED

3 new-to-me brands with beautiful dresses

Sometimes you need something a extra special, like this gorgeous belted number that looks like something Audrey Hepburn would wear in “Roman Holiday,” a red and purple ric rac dress that’s playful and fun or a checked dress that’s modeled after a traditional dirndl.

GOOD CHOICE

Pretty handkerchiefs to carry everywhere

I have a handful of handkerchiefs, mostly gifts from my grandmother, tucked in a drawer in my bedroom for safe and accessible keeping — and one in my purse, too. Whether you’re a cryer or get watery eyes from allergies, a beautiful handkerchief is great to have in hand. You can find pretty patterned ones at Liberty London or embroidered ones all over Etsy.

All the best,

Mary Grace